This is the fourth post in my family culinary history series. To start from the beginning, please see my Connecting with my Ancestors through their Recipes post.

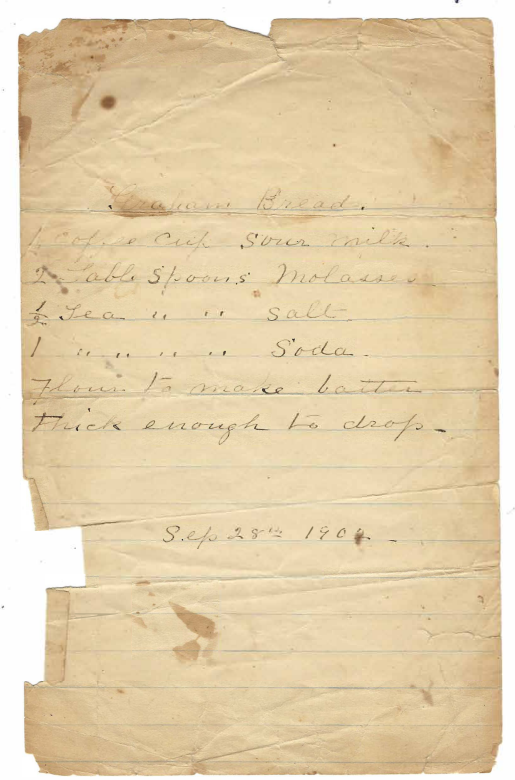

Graham Bread

1 coffee cup sour milk

2 tablespoons of molasses

½ teaspoon of salt

1 teaspoon of soda

Flour to make batter thick enough to drop

Sept 28th, 1902

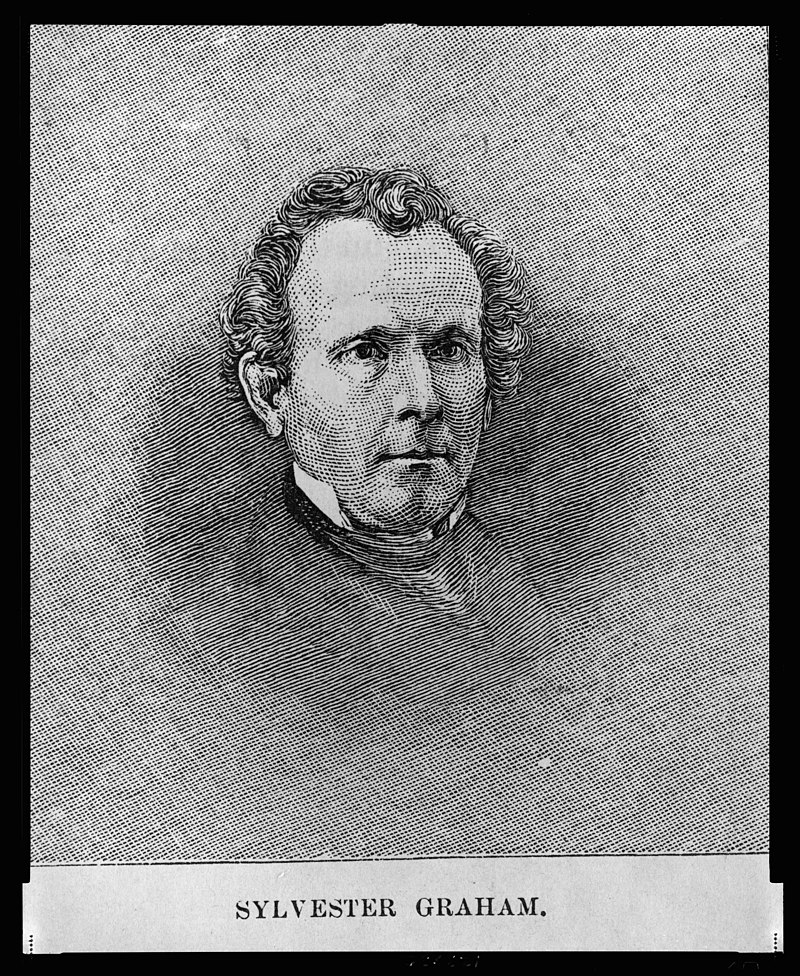

Sylvester Graham

Graham bread (and yes, graham crackers too) is named after Sylvester Graham, who lived from 1794 to 1851, was a minister with extremely ardent opinions on appropriate diet and nutrition. He was strongly against the industrialization and commercialization of life at the time and proposed a regime of strict dietary and sexuality controls as a remedy for social ills.

The Science of Human Life

Graham’s perspectives on bread and baked goods were particularly influential. According to McWilliams (2008):

Graham’s definition of ‘good’ bread grew out of his belief that ‘food in its natural state would be the best’ for human health. Ideally, food should be processed as little as possible; indeed, Graham claimed that uncooked food was not only best for dental and digestive health but also closest to the divine plan. […] Graham echoed the common complaints about adulteration by commercial bakers. But he added a unique twist: even the best bakery bread was doubly flawed. The flour itself was inferior because it was over-processed, according to Graham: the ‘superfine flour’ required for white bread ‘is always far less wholesome, in any and every situation of life, than that which is made of wheaten meal which contains all the natural properties of the grain.’ The fine flour results when ‘human ingenuity tortures the flour of wheat’ rather than leaving it in its natural state.

Graham even insisted that families wait to hand-grind their flour just before using it in baking! While graham crackers have evolved very far from Graham’s vision into something he would probably find abhorrent, graham bread and flour has more or less stayed true to his philosophy.

The question becomes, why did my great-grandmother have a recipe for graham bread in her cookbook? Was she a believer of his philosophy or was it just a popular recipe during the time? As the other recipes in her cookbook would most likely horrify Graham, I can only assume it was more the latter than the former, but I can only guess.

Recreating this recipe was a bit of a challenge for a number of reasons: the “coffee cup” unit of measurement, tracking down ingredients such as “sour milk” and graham flour (which I assumed was the type of “flour” intended), the lack of any real instructions including baking temperature or time

Coffee Cup

After some research, I found an article by Green (2018) which seemed to suggest that a “coffee cup” was the equivalent of about a quarter of a cup.

But right before making the recipe I started to feel like something was not right, and after a quick Google search I found other sources which equated it as a full cup, which made more logical sense.

Sour Milk

Apparently, sour milk is different from modern buttermilk and was actually milk that was left out to ferment slightly, probably a common occurrence due to limited refrigeration technology.

My assumption is that the chemical reaction between the baking soda and the acidity in the sour milk is what leavens the bread since there are no other leavening agents in the recipe.

I was a bit nervous about leaving milk out to sour, so instead I used a shortcut by adding a little lemon juice to whole milk and letting it sit for five minutes before using (Blue Flame Kitchen, 2022).

Graham Flour

I really wanted to use actual graham flour for this recipe to truly replicate the dish as it was intended, but despite searching five different physical stores and multiple online stores I could not find graham flour in a quantity or price point that made sense.

Filippone (2022) recommended unbleached, unrefined whole wheat flour as a good substitute, which I already had on hand, so I ended up just using that.

As for the amount, I used Caranna’s (2020) three cups graham flour or whole wheat flour as a guide; however, I ended up only using two and a half cups of flour as the dough was already starting to feel quite thick.

Directions

According to the White House Cookbook, there are at least two main versions of graham bread, unfermented and fermented (Sutherland, Schulze, and the Distributed Proofreaders Team, 2004). As the ingredients for the unfermented version matched my great-grandmother’s recipe more closely, I used it as a guide for the order of operations.

Basically, the instructions were:

Sift together dry ingredients. Mix molasses and sour milk together. Combine wet and dry mixtures and bake in greased loaf pans.

However, it still did not include oven temperatures or time, so I again went pack to Caranna (2020) and ended up baking the bread at 350 F for 30 minutes (checking on it after 15 minutes just in case).

Video and Tasting!

Updated Recipe

Irene Caron’s 1902 Graham Bread*

1 cup milk

1 tsp lemon juice

2 tablespoons molasses

½ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon baking soda

2 ½ cups graham flour or whole wheat pastry flour

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Grease one loaf pan. Combine lemon juice and milk in a small bowl, set aside for at least five minutes. After five minutes, mix the molasses into the soured milk until combined. In a separate bowl, sift together the salt, baking soda, and flour. Add the flour to the molasses-milk mixture and stir until fully mixed. Pour into prepared pan and bake for 30 minutes or until a toothpick inserted into the bread comes out clean. Let cool on a wire rack.

*Sept 28th, 1902

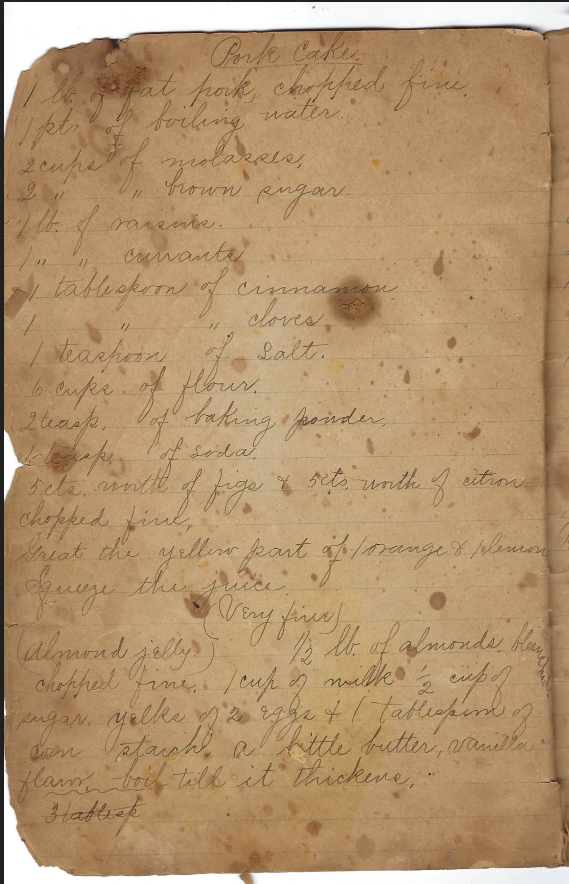

Next Steps: Pork Cake!

The next steps in this project are to make my great-grandmother’s recipe for Pork Cake!

To read about my experiences making that recipe and the struggles I overcame while doing it you can read my Irene’s Recipes #5: Pork Cake: Communing With My Great-Grandmother Through Her Recipes post!

Resources

Blue Flame Kitchen. 2022. “How to Make Sour Milk.” Blue Flame Kitchen. Date accessed November 1, 2022. https://www.atcoblueflamekitchen.com/en-ca/how-to/make-sour-milk.html#:~:text=%E2%80%8BHow%20to%20Make%20Sour%20Milk&text=To%20make%201%20cup%20(250,for%205%20minutes%20before%20using.

Caranna, Angel. 2020. “Graham Bread, Temperance Reformers, and America’s First Fad Diet.” University of Michigan. Last modified May 26, 2020. Date accessed October 28, 2022. https://apps.lib.umich.edu/blogs/beyond-reading-room/graham-bread-temperance-reformers-and-america%E2%80%99s-first-fad-diet

Filippone, Peggy. 2022. “What Is Graham Flour? A Guide to Buying and Baking With Graham Flour.” The Spruce Eats. Last modified September 19, 2022. Date of access November 1, 2022https://www.thespruceeats.com/graham-cracker-and-flour-history-1807555

Green, Denzil. 2018. “Measuring Cups.” Cook’s Info. Date of access November 5, 2022. https://www.cooksinfo.com/measuring-cups

McWilliams, Mark. 2008. Moral Fiber: Bread in Nineteenth-Century America. In Food and Morality: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cooking, 2007, ed. by Susan R. Friedland, 184-193. Devon: Prospect Books.

Sutherland, Juliet, Stephen Schulze, and the Distributed Proofreaders Team. 2004. “Project Gutenberg’s The Whitehouse Cookbook (1887), by Mrs. F.L. Gillette.” Project Gutenberg’s The Whitehouse Cookbook (1887), accessed October 23, 2022: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13923/13923-h/13923-h.htm#Page_282